Now, if like me, you have suddenly found yourself on a Eurostar last week, bound for Paris at the tail end of the first term, finishing the last of your coursework, while rushing to embrace friends and family, to mark Catholic Christmas, Hanukkah and other holidays under the bells of Notre-Dame, I assume you have long been craving an escape from the city’s incessant shimmer of lights, rain and endless chatter. These three Parisian exhibitions offer exactly that. They unfold as quiet meditations after a demanding working season and stand out as rare moments of calm worth sinking into this winter.

Fondation Louis Vuitton welcomes visitors with a rare attentiveness through an exhibition devoted to Gerhard Richter, arguably one of the most influential and productive artists of the present day. Richter has long insisted that all human response is shaped not by what is seen but by how it is seen, and this idea runs silently through the retrospective, organised in close collaboration with the artist, who turned ninety-three this year. The exhibition is curated by those who have known his work closely over decades, including Sir Nicholas Serota, predecessor to the recently departed Tate director Maria Balshaw, and Dieter Schwarz, curator and artistic director of the Kunstmuseum Winterthur in Switzerland. Room by room, Richter’s familiar language unfolds without insistence. Blurred portraits drawn from photographs refuse fixed identity. Abstract canvas’ flare with colour and then withdraw. Landscapes appear without promise of beauty, selected by an internal logic that resists explanation. As the visitor moves through the exhibition, available to view until 2nd of March 2026, Richter seems to test the edge of the visible world, searching for the moment where form no longer holds and perception quietly takes over.

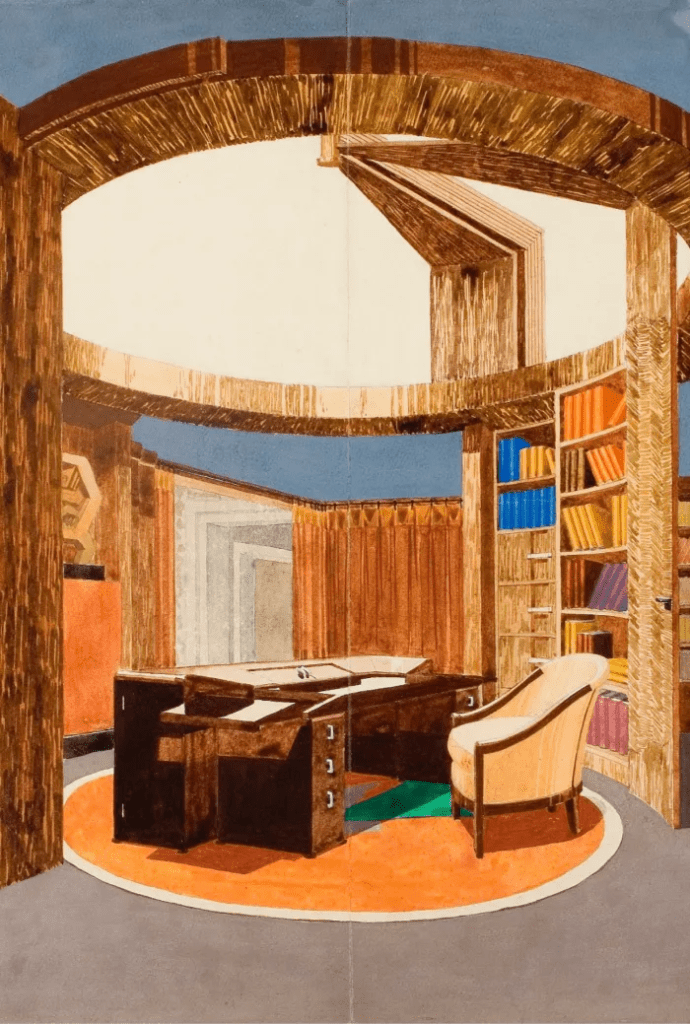

Musée des Arts Décoratifs devotes a large-scale exhibition to Art Deco, tracing its trajectory from the International Exhibition of 1925 through to the present day. Spread across three floors, the curators have assembled more than twelve hundred objects of furniture, jewellery and dress, interwoven with posters, drawings and everyday accessories of the period. The galleries are thick with original decorative elements and fragments of lavish interiors. I was immersed into the visual culture of the 20s and 30s. Labels guide the eye toward recognised names in interior design, and toward materials that were once radically new. Poised armchairs, deep carpets, Lacquered marquetry panels, silver cocktail shakers resting in bars, shagreen leather and sacred geometry of form and line – all converge into a single microcosm of cultivated luxury. Everything belongs to an interior imagined as a total work, expensive and measured, opulent and controlled. The exhibition runs until 26th of April 2026, yet it is in the festive season that it should be seen. After the pressure of recent academic deadlines, it offers a lowering of pace, even of breath. One enters the domestic, almost childlike worlds of Ruhlmann, Gray, Frank and Chareau, where the careful orchestration of interiors and the density of detail produce a quiet harmony, one that gently retunes the senses for the festive season.

Pinault Collection at the Bourse de Commerce, recently transformed by Tadao Ando, the world’s most influential self-taught Japanese architect, steps next door into minimalism itself with an aptly titled exhibition ‘Minimal’. Just over a hundred works are gathered and organised here into seven thematic groups defined by visual formal qualities: Light, Balance, Surface, Grid, Monochrome, Materialism, and the lesser-known Mono-ha, or the School of Things. Emerging in Japan, Mono-ha shifted attention away from narrative and expression toward material and space, seeking to examine matter itself and the relationships that arise between these two elements. The exhibition traces the evolution of these strands of minimalism from the 1960s to the present day, while situating them within a broader, global context. Until the 19th of January 2026, works by Japanese artists unfold alongside the quiet force of Italian Arte Povera and the German collective Zero, their restrained vocabularies meeting on equal ground and revealing how minimalism, across geographies, learned to speak through stillness.

Edited by Saffron Watkins

Cover Image:

The installation ‘Prologue’ by Mathilde Bretillot, at the ‘Les Nouveaux Ensembliers’ salon, at the Mobilier national (Image: Le Monde)

Leave a comment