I first saw Il Trovatore at Frieze London on a day when the fair felt especially loud. People drifted in and out of booths, discussing contemporary artists, as I watched the strange distortions of the tent. Dozens of viewers beelined across curated walls. I turned into a quieter corner of the Hauser & Wirth presentation to then face Il Trovatore.

When describing his work, George de Chirico once said that his paintings from this period “provoke a feeling of profound dizziness, typical of metaphysical visions.” My day at Frieze both began and ended before the same mannequin, letting that dizziness settle in. It wasn’t vertigo, but something subtler: a quiet destabilization that felt all encompassing, a painting that felt equally dated as it did current.

Painted in 1950, during de Chirico’s metaphysical period, Il Trovatore sits just outside of Surrealism. Although later embraced by the Surrealists as a kind of precursor, he never truly belonged to their movement. Where Surrealism leaned into dreamlike logic, de Chirico approached his strangeness through structure, borrowing from architectural thinking and ultimately producing clarity through his distortions.

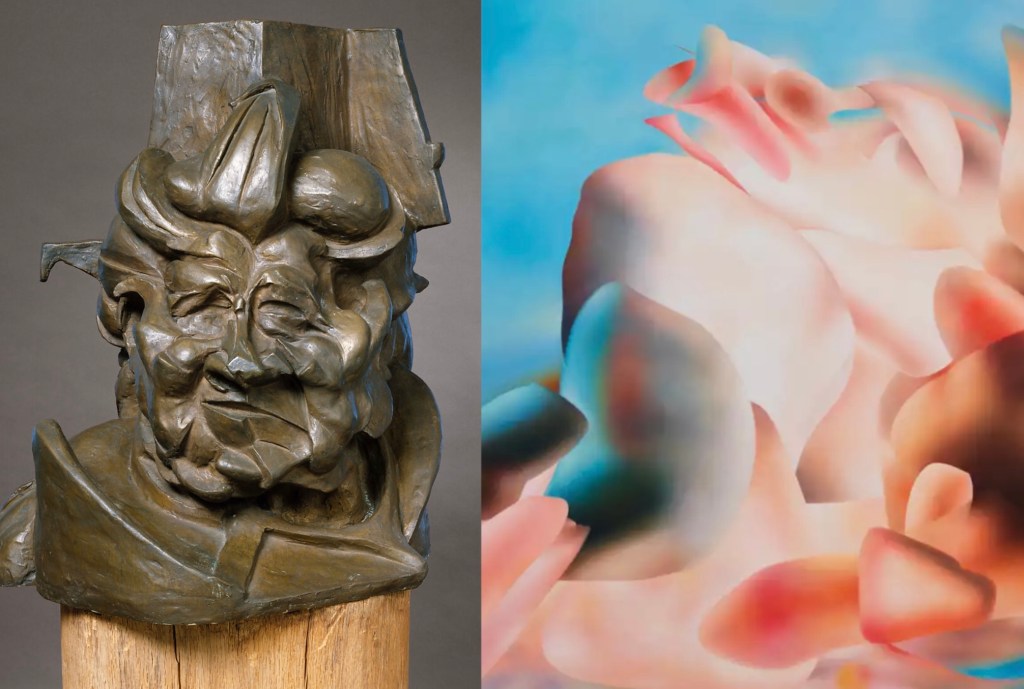

In Il Trovatore, the body is only loosely a body. The limbs are wooden, jointed, and architectural. The torso is a collage of geometric plates. The face is an oval mask without features, stitched together like a seamstress’s pattern. He’s a troubadour, but a hollow one: a performer whose instrument is missing and whose voice has never existed. The entire composition feels theatrical and staged, uncanny in its stillness—an encounter with a figure that is not alive, yet too central for the background to command any attention.

While Il Trovatore belongs to the postwar period, what kept pulling me back was how suddenly relevant it felt. The mannequin’s body is assembled, optimized, detachable. It plays openly with the transhumanist fantasies that exist today: the modular self, the upgradable self, the scanned-and-simulated self. De Chirico’s figure is not yet a machine, but he is no longer fully human. He stands in the liminal space between what a person is and what a person might become, where the boundaries of the self feel suddenly negotiable.

Looking at Il Trovatore, I found myself reverberating with the feeling of how art from a century ago can feel attuned to our current moment. Not because it predicts the future outright, nor because de Chirico was thinking about our techno-optimist futures, but because it identified a psychological atmosphere we have only recently stepped into, one in which identity can be suspended, paused, and rearranged. In all of its strangeness, Il Trovatore offers us the reminder that art has long been able to register psychological horizons before we fully can.

Edited by Alison Grace Zheng

Leave a comment