Maurice Denis, born on November 25 in 1870, was a French painter, writer, founder of the Nabi movement and its influential theoretician. His seminal work on art theory, aesthetics and spirituality contributed to the formation of key 20th century art movements including favism, cubism and abstract art. Today Paper Galleries celebrate Denis’s 155th birthday, his love of Christian miracles, Paul Gauguin, brightly coloured forms, ancient mythology, music and the sea by revisiting some of his most idyllic artworks (and our personal favourites).

Any artist who lived in Paris during the late 19th and early 20th century was passionate about painting nude priestesses of love and defying societal norms. Denis’s breakaway from this canon and his earnest determination to revitalise sacred art in France became apparent during his early years within the walls of École des Beaux-Arts. At 18, Denis gives a modern feel to the traditional story of the Annunciation. He depicts it distinctively mundane, replacing Archangel Gabriel with a Catholic priest, who stands unwaveringly in front of the blessed mother with an open book and two child servants holding candles. The scene shows whitewashed walls and a curtained window overlooking a tranquil countryside landscape. Denis applies swabs of colour separately, defines contours, constructs symbolist composition and abstains linear perspective reminiscent of Les Nabis’ paragon – Paul Gauguin: his use of pure color, flat surfaces, and symbolic, non-naturalistic approach to painting.

I have to be a Christian painter, I have to celebrate all the miracles of Christianity, I feel I have to’ – The enchantment with New Testament narratives most likely follows from the profound religiosity of the artist’s family. In Let the Children Come to Me, the trembling chiaroscuro looks like it is casted by the flame of church candles, and the slight mist that hangs in the painting feels lifted by the thick, mingled incense smoke. In a monastery garden in his hometown Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Denis kneels before Christ. By giving Jesus features of a familiar presence, he translates the sacred ritual of First Communion into the realm of the domestic, drawing a scene from Scripture into the family circle.

The richness and purity of Gauguin’s colour choices would shape Denis’s work for the rest of his life. As one of the guiding figures for the Nabi group, Gauguin offered lessons and direction – with slightly different words on several occasions – ‘How do you see this tree? Is it really green? Use green, then, the most beautiful green on your palette. And that shadow, rather blue? Don’t be afraid to paint it as blue as possible’.

In Women Sitting on the Terrace, Denis keeps the bright, pure colours, simple forms outlined with a soft black framing, but introduces a wide canvas typical of japonism, decorative patterns and a calm everyday French setting. There is not a single trace of suffering, everything radiates. Gardens, children, and the quiet presence of women.

In a later work, The Muses, Greek mythology starts to appear within Denis’s thematic scope. The scene shows a forest in Saint-Germain, which Denis often referred to as his own sacred grove. The Muses, known as the protectors of the arts, are presented here as an allegory to the central ideas that guide his practice. The figures do not carry the objects that would normally show which Muse is linked to which art or science. Neither they possess any other distinctly mythical feature. This trick, just like with Jesus from Let the Little Children Come to Me, underpins how Denis sought to place the divine within the everyday. Muses are humane, gentle, flowing and seated quietly in the shade of a chestnut grove.

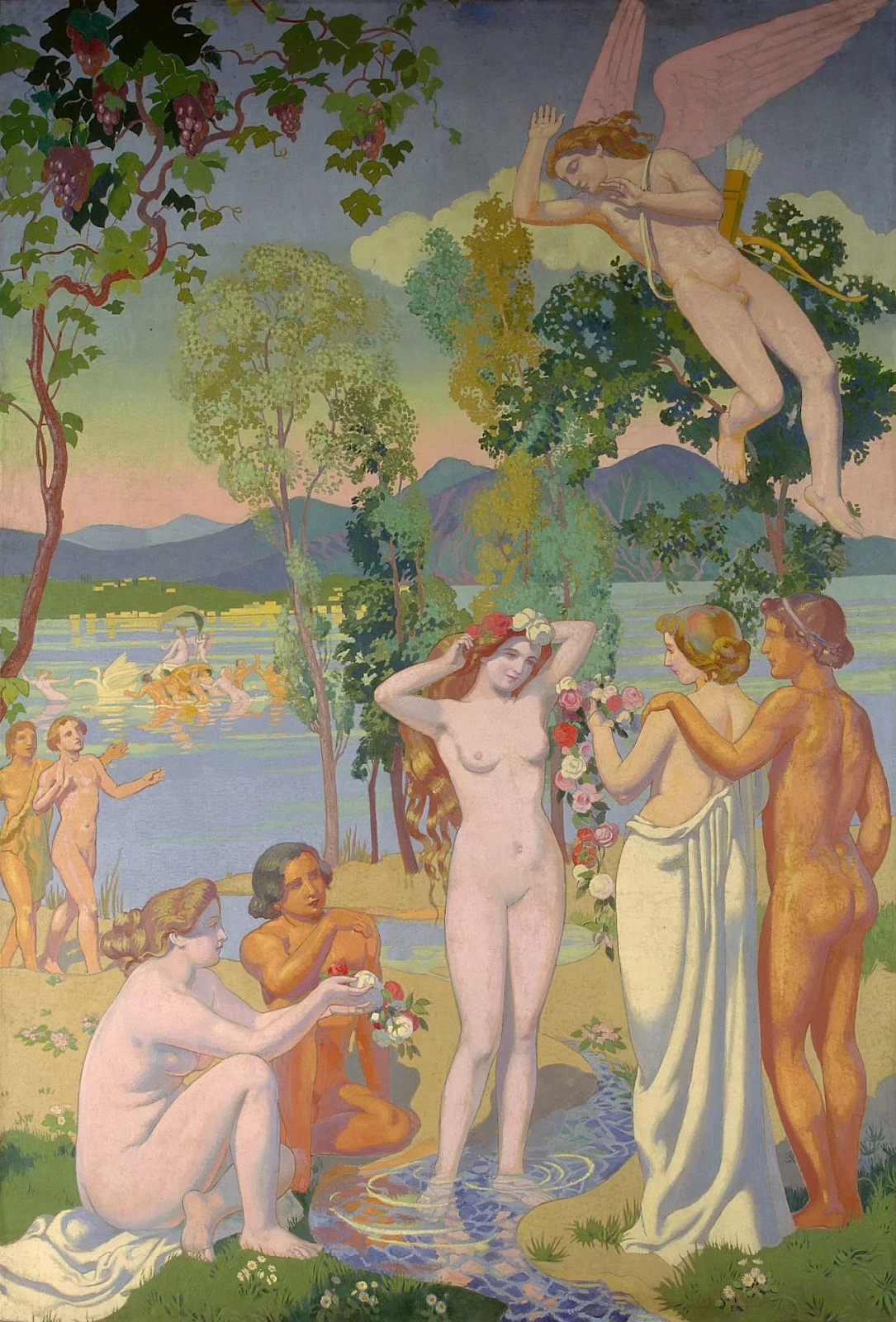

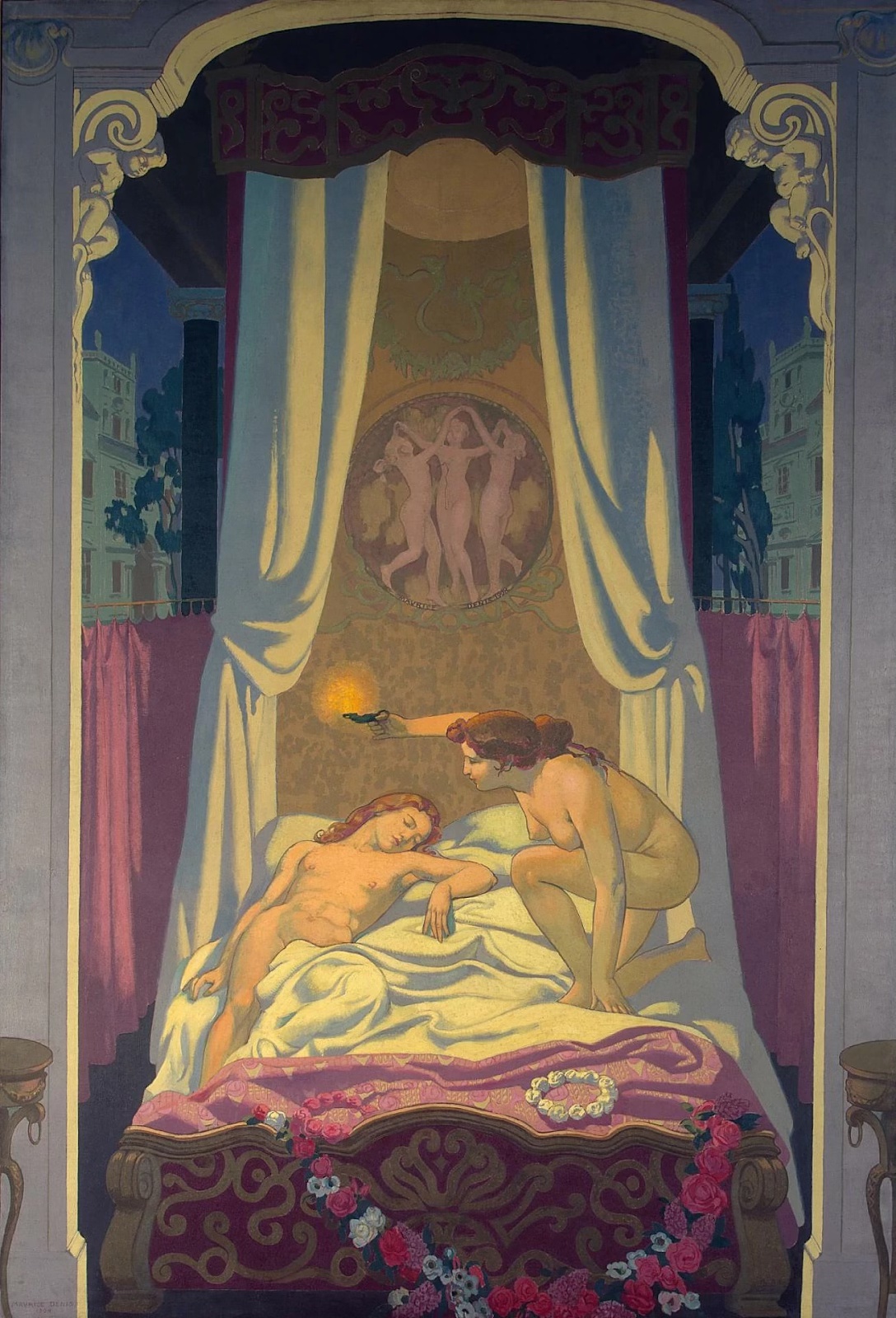

Maurice Denis, The Story of Psyche (left to right: panel 1 – Eros is Struck by Psyche’s Beauty, panel 2 – Zephyr Transporting Psyche to the Island of Delight, panel 3 – Psyche Discovers that Her Mysterious Lover is Eros, panel 4 – The Vengeance of Venus, panel 5 – Jupiter Bestows Immortality on Psyche) (1908), oil on canvas, 1 – 394×269.5cm, 2 – 395×267.5cm, 3 – 395×274.5cm, 4 – 395x272cm, 5 – 399x272cm, Images: arthistoryproject.com

Denis begins to engage with ancient mythology more openly as his work develops. In 1907 the Russian patron Ivan Morozov commissioned him to create a series of panels The Story of Psyche for his private residence. All varying in size, they recount the ancient Roman myth in five episodes, telling the love story of Eros and Psyche, in which Eros represents love and Psyche – the soul.

Commissioned by the same patron, the painting Polyphemus reveals the same intertwining of reality and myth. In ancient stories the one-eyed Cyclops, son of Neptune and a sea nymph, lived in a cave at the foot of Mount Etna and devoured humans. In Denis’s painting he is given an idyllic role as a gentle sea deity. Among a group of bathers on the beach, the figure of Polyphemus appears with his back turned to the viewer, playing a pipe.

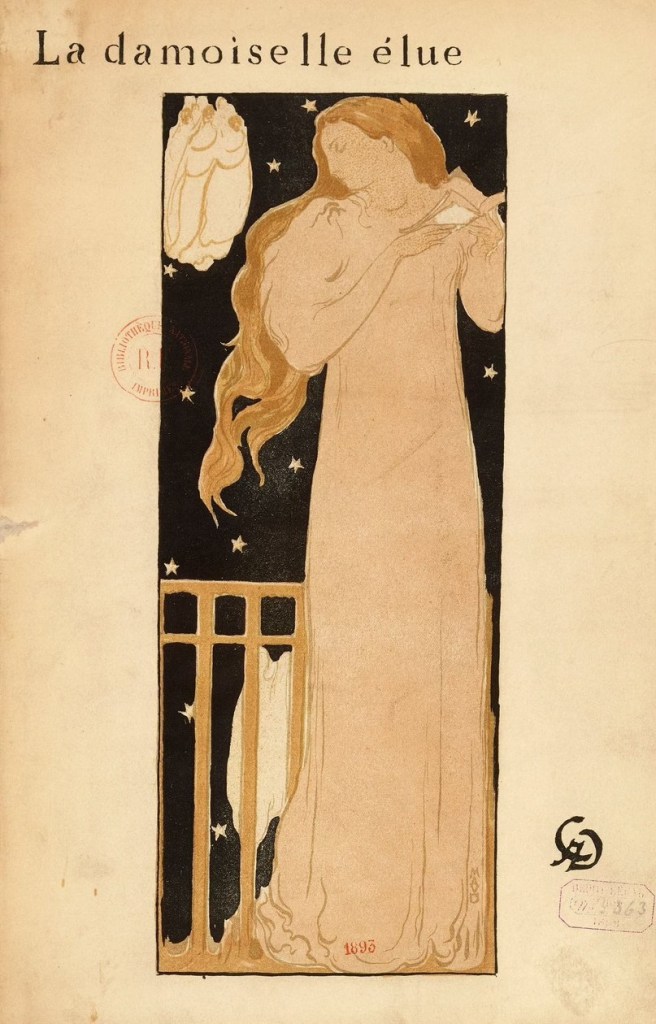

Music runs like a red thread through Maurice Denis’s oeuvre. It appears in the subjects of Le Menuet de la Princesse Maleine, Procession de Fete Dieu and in his sheet-music cover for Claude Debussy. But beyond that it shows in the musical rhythm of his smooth, airy lines, round composition and enigmatic mood. Realism is prose and he aims for music.

Further Reading:

Coombes, Rachel. “MAURICE DENIS’S THE HISTORY OF MUSIC: ALLEGORISING CULTURAL TRADITION IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY FRANCE.” In Belonging, Detachment and the Representation of Musical Identities in Visual Culture, edited by Antonio Baldassarre and Arabella Teniswood-Harvey, 395–422. Hollitzer Verlag, 2023. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.5211766.19.

Leave a comment