In recent weeks, I was introduced to the work of Ketty La Rocca, currently exhibited in the light, snug rooms of the Estorick Collection in Canonbury, Islington. Ketty La Rocca – one of the leading Italian feminist artist of her time, whose life was tragically cut short at just thirty – explored gendered social realities and the role of the female body within them. However, what sparked a deeper curiosity in me was La Rocca’s experimentation – or rather continuous collaboration – with written language and syntax, reinforced through the synthesis of pictorial and textual realms, brining two media together to create a more layered message.

La Rocca’s interest in text seems to originate in the socio-political environment of the post-war Italy, during the period known as Years of Lead (1968-1980). Central to the massive social upheaval was the rapid development of mass media – newspapers, magazines, and television – with a focus on socio-political observation, but not limited to such, with developing lifestyle publishing such as Epoca and Oggi, and a growing sphere of advertising. An art historian Gangemi Rosanna succinctly described this moment as an epoch of “liminality of the word-image and logo-iconic interactions.” Language thus became a source of power – to sell, to propagate, to subjugate, and to liberate, and Ketty understood it acutely.

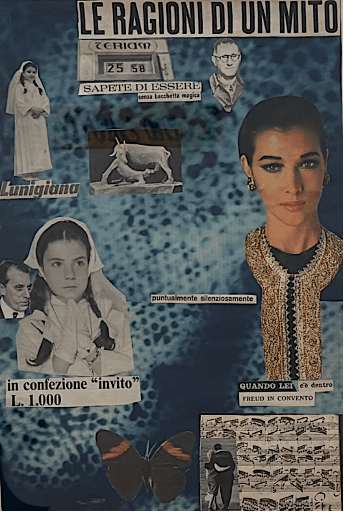

La Rocca’s collage work Le Ragioni di un Mito (The Roots of a Myth) incorporates metaphor and vague allusion through the semantic ambiguity between image and text. For example, a magazine cutout image of a girl praying is placed above the text reading: “In confezione invito L. 1000” (“in invitation package for a price of 1000 lire”), turning an image of sacred piety into a commodified object that “invites attention”. This is likely a pun on ‘invito alla confessione’ – ‘invitation to confession’ – turning the mirror to society, poking at the remnants of heightened religiosity of the 60s-70s along the ubiquitous sexualisation and objectification of women.

The next cutout is of a fashionably made-up woman nearby, wearing a golden vest reminiscent of a liturgical orphrey. The text below reads: “Lei c’è dentro, Freud in convento” (“When she is into it, Freud is in the convent”), alluding to the popular notion of female hysteria and the ‘abnormality’ of women’s active expression of own interests and desires. Other messages such as “sapete di essere senza bacchetta magica” (“you know you are without a magic wand”), and an image below of a classical statue of a goat suckling her kid continues the message of “second gender” and points to women’s traditional ‘priorities’ as motherhood. Using a mixture of cutout visual and verbal information from everyday media like magazines, La Rocca not only solidifies the connection of the contemporary realities of life but also demonstrates how the synthesis of both can manipulate the overall message.

In some works, La Rocca goes as far as to showcase a disintegration of the solid structure of not only the sentence but an image itself. Her Riduzioni polyptychs show a gradual ‘molecularization’ of an image into flowing sentences that reconstruct it outline, sometimes reducing it further into single words such as ‘You’, and ultimately into simplified silhouette composed purely of pictorial symbols.

This suggests a certain point of convulsion – an epistemological shift, stripping the image of – first, its cover, to then simplifying its sacred meaning to the point of the primitive which leaves the viewer with a sense of an afterimage or a memory. Her dismantling of meaning has affinities – with no claim of direct influence – with other avant-garde attempts to reach the primordial core of language.

In a sense it may remind one of the technicalities of Zaum poetry, which having grown under the influence of Futurism originated in Italy, and achieved its final form in the early years of Soviet Union, wanted to delve even beyond the rational language into the intuitive, with one of its tactics being a disintegration of language to its primal understanding – the most sacred reading of it. A word – as Xlebnikov said – “is a self-sufficient force which organizes the material of feelings and thoughts”, and La Rocca seems to embrace this notion in using ‘You’ as a beginning and ending of every story.

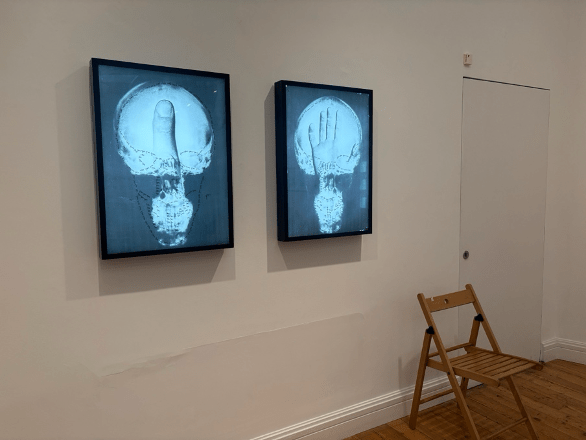

In another Craniologia series, made up of enlarged X-ray images of her skull filled with a repeated word of ‘you’ and superimposed with the artist’s hands, Katty la Rocca starts to mix both traditional letter signs with her non-verbal ‘universal’ gesturing. This series feels more contemplative not only because of its ambiguity and minimalistic composition, but also because of the personal context: at the time, Ketty had been diagnosed with a brain tumour. It was perhaps this technology of radioactive waves that penetrate the deepest layers of the human body and make the hidden visible, that La Rocca found inspiration from to represent the search for one’s own voice inside the female mind.

The repeated ‘You’ reappears as an inward dialogue; the pointed finger may symbolise attention, while the open palm invites for slowing down, greeting or honesty. A literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin in his theory of heteroglossia would say: “Apart from the communication between one human and another, speech is a necessary condition for reflection even in solitude”. By staging the self as both speaker and listener, the work reflects Bakhtin’s argument that inner speech is dialogic by nature. Therefore, the work can be read as a female search for agency, outside of the imposed expectations and limitations onto its flesh.

La Rocca’s art exposes how language shapes the way women are seen – and how it can be undone. By cutting, reducing, and reworking signs, she turns fragments into a new form of speech.

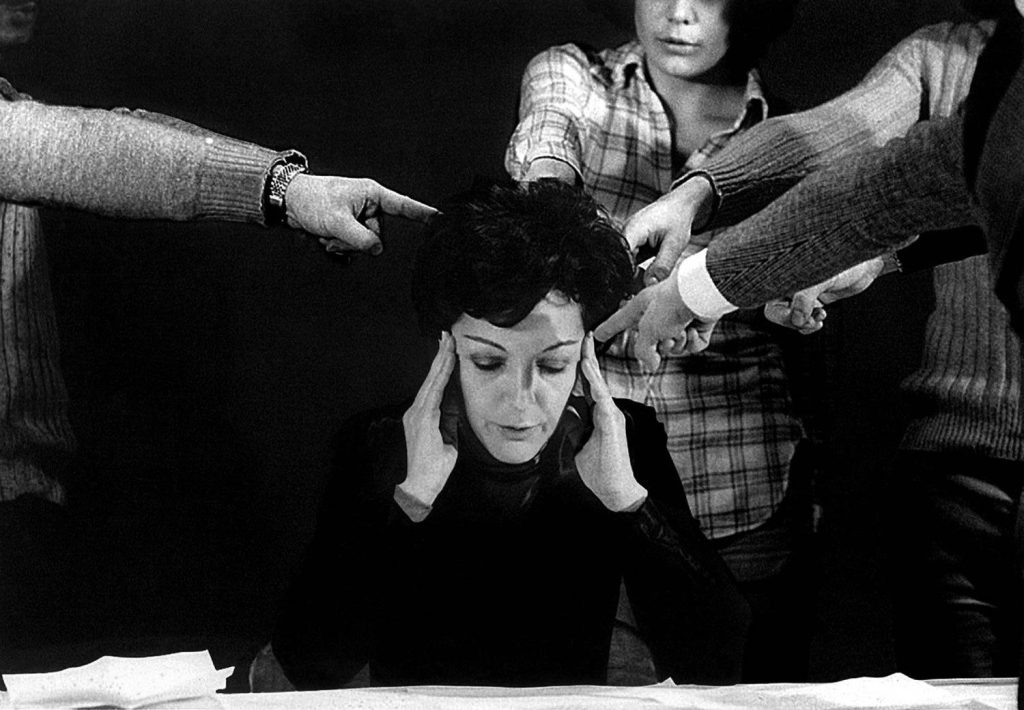

The cover image is from Ketty La Rocca, La mie parole et tu [my words and you], 1975, performance, galerie Nuovi Strumenti, Brescia – via: https://awarewomenartists.com/en/artiste/ketty-la-rocca/

Leave a comment